Business Processes as Types, Let's Explore

// date: 2022-05-17

// filed: golang, programming

// perma

A conversation arose where business processes as type safe mutators is possible but too complicated to do in practice. It doesn't have to be and, in fact, isn't that difficult to do if you spend some time thinking prior to hamfisting the keyboard.

Usually what is found on the subject is something easy to do that might fail at some point and then you're on your own. The boilerplate is difficult to read, the difference in thinking from standard ways of doing things is glossed over, and you've wasted 15 minutes trying to understand what the author is thinking.

For this article we're going to focus on:

- readability

- ergonomics

- no more

if err != nil ...litter

Building a Foundation

We need a different way of thinking about our problems, it's very

familiar but a weird concept in programming to think: "we'll try to do

something, see if there's an error, try to do something

else, see if there's an error" and so on. Let's start thinking

about problems in a way that is "let's perform some setup, try to

perform our process, and then handle any errors that happened

at any point during the operation". In order to do this we're going to

have to think about what data is required to perform some operation and

then allow methods to fail while still mutating the output to the next

expected input. This is something functional languages get for free and

some are better at it than others, in go we can write our own

Either type (in either/either.go):

package either

type WHICH int64

const (

LEFT WHICH = iota

RIGHT

)

type Either[L, R any] struct {

isLeft bool

left L

right R

}

type EitherInterface[L, R any] interface {

Which() WHICH

Left() L

Right() R

}

func Left[L, R any](l L) Either[L, R] {

return Either[L, R]{

isLeft: true,

left: l,

}

}

func Right[L, R any](r R) Either[L, R] {

return Either[L, R]{

right: r,

}

}

func (e Either[L, R]) Which() WHICH {

if e.isLeft {

return LEFT

}

return RIGHT

}

func (e Either[L, R]) Left() L {

return e.left

}

func (e Either[L, R]) Right() R {

return e.right

}Now we're cooking. The Either type gives us

LEFT|RIGHT branches. There exists many ways to use this but

for this article we're going to assume that once our object is in the

RIGHT branch we do not want to further process. It also

takes advantage of generics so that you do not have to write the same

code over again with all of your types.

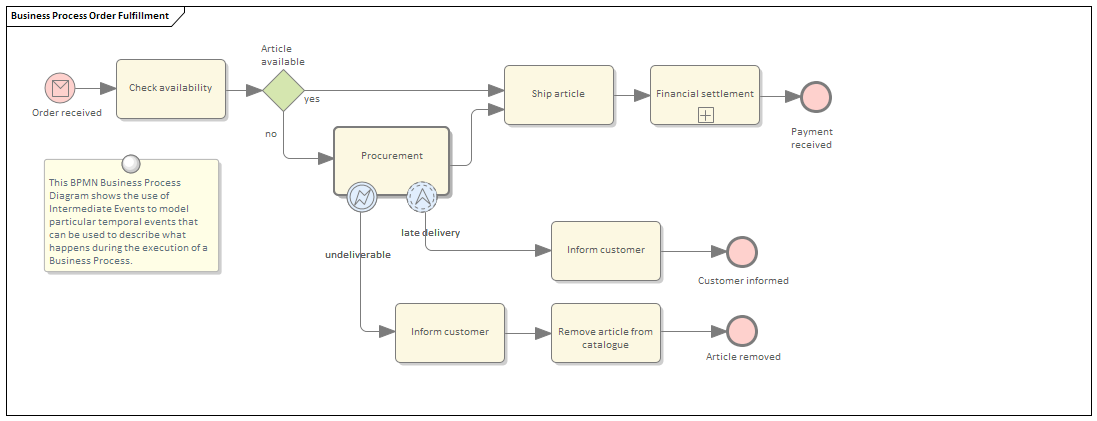

Business Processes

Let's do something more complicated than your usual. This is

non-trivial but you'll see it can be boiled down to a call

chain that is easily debugged, easy to read, and looks like

.Quantity(itemID).Procure(itemID, qty).Ship(itemID, qty).Invoice().

Wowsers, let's write our example inventory system. Obviously, in

practice, the signatures here would change and you'd have stuff like an

address to ship to. In inventory/inventory.go:

package inventory

import (

"github.com/pkg/errors"

"deathbykeystroke.com/either/either"

)

// Our Demo _DB_ - no promise of thread safe or anything else

type Inventory struct {

onHand, onOrder int

}

var inventory map[int]*Inventory = map[int]*Inventory{

10: &Inventory{onHand: 100},

20: &Inventory{onHand: 50},

30: &Inventory{onHand: 1},

40: &Inventory{onHand: 0},

}

// Track an order result so that later we may notify the customer

type OrderResult int

const (

UnableToProcure OrderResult = iota

Ordered

Fulfilled

)

var OrderResultStrings = map[OrderResult]string{

UnableToProcure: "Unable to procure",

Ordered: "Ordered",

Fulfilled: "Fulfilled",

}

// Create types and implement the EitherInterface so that we can use the Either[x,y] as receivers

// and maintain type/mutation safety in our call chain.

// We really want the compiler to ensure that our (in -> out) matches our chaining pattern.

type InventoryQuantity either.Either[*Inventory, error]

type InventoryOrderResult either.Either[OrderResult, error]

type InventoryProcurementResult either.Either[Inventory, error]

func (i InventoryQuantity) Which() either.WHICH { return either.Either[*Inventory, error](i).Which() }

func (i InventoryQuantity) Left() *Inventory { return either.Either[*Inventory, error](i).Left() }

func (i InventoryQuantity) Right() error { return either.Either[*Inventory, error](i).Right() }

func (i InventoryOrderResult) Which() either.WHICH {

return either.Either[OrderResult, error](i).Which()

}

func (i InventoryOrderResult) Left() OrderResult { return either.Either[OrderResult, error](i).Left() }

func (i InventoryOrderResult) Right() error { return either.Either[OrderResult, error](i).Right() }

// Quantity retrieves an inventory object from our "db"

func Quantity(id int) InventoryQuantity {

if inv, ok := inventory[id]; ok {

return InventoryQuantity(either.Left[*Inventory, error](inv))

}

// We return a RIGHT value here so whatever the consumer is knows this is a failed value,

// remember: we're ignoring RIGHT values and handling the error all at once regardless of

// what threw the error.

return InventoryQuantity(either.Right[*Inventory, error](errors.Errorf("no record of id: %d", id)))

}

// Procure short circuits on RIGHT and because `i` is already in a failure state, we just move

// down the chain because Procure has no business handling an error in its caller.

func (i InventoryQuantity) Procure(id, n int) InventoryQuantity {

if i.Which() == either.RIGHT {

return i

}

invN := i.Left()

if id >= 30 && invN.onHand < n && invN.onOrder < n {

return InventoryQuantity(either.Right[*Inventory, error](errors.Errorf("cannot order id: %d", id)))

} else if n > invN.onHand {

// do some procurement process

(*invN).onOrder += n

return InventoryQuantity(either.Left[*Inventory, error](invN))

} else {

return InventoryQuantity(either.Left[*Inventory, error](invN))

}

return InventoryQuantity(either.Right[*Inventory, error](errors.Errorf("no record of id: %d", id)))

}

// Ship reduces the inventory quantity onHand or onOrder depending on what is available, again

// ignoring any RIGHT sided Either

func (i InventoryQuantity) Ship(id, n int) InventoryOrderResult {

inv := i.Left()

if i.Which() == either.RIGHT || (inv.onHand < n && inv.onOrder < n) {

return InventoryOrderResult(either.Left[OrderResult, error](UnableToProcure))

}

if inv.onHand >= n {

(*inv).onHand -= n

return InventoryOrderResult(either.Left[OrderResult, error](Fulfilled))

}

(*inv).onOrder -= n

return InventoryOrderResult(either.Left[OrderResult, error](Ordered))

}

// Invoice should create an invoice somewhere for the customer. In reality Quantity should be

// gathering the related inventory and then either the caller or some process should be enriching

// this object with the customer data.

func (i InventoryOrderResult) Invoice() InventoryOrderResult {

if i.Which() == either.LEFT && i.Left() == Fulfilled {

// Create an invoice

}

return i

}

// String returns LEFT -> enum as a string, RIGHT -> error as a string

func (i InventoryOrderResult) String() string {

if i.Which() == either.RIGHT {

return i.Right().Error()

}

return OrderResultStrings[i.Left()]

}There's a lot to unpack in this code. First, we create our inventory

- a map that contains our inventory info. Then we create our types of

Eithers, then we create the receiver functions that can

operate on those types. Each step is commented in the code to give

clarity while the code is being read. You'll notice that each

func with an Either receiver short circuits on

a RIGHT value. This is desirable so we don't break our

chain and it's something that pattern matching functional languages get

for free. We don't so we'll do it this way for now. Another tactic for

getting this is writing Lifters that can take pure

functions and essentially add/remove the value from our

Either. We're not going to do that right now because go's

support for generics and receivers is not great.

From the function signatures you'll see that you can chain together

everything as: .Quantity.Procure.Ship.Invoice and no matter

what state our order is in, if the item is unattainable or not

available, nothing happens to the inventory, and no invoice

will be generated.

Putting Our Design to Use

Let's write a test to see if we get what we expect, in

main.go:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"os"

"deathbykeystroke.com/either/either"

"deathbykeystroke.com/either/inventory"

)

// Order !! Our business process as a type safe, readable, and reliable call chain:

func Order(id int, n int) inventory.InventoryOrderResult {

return inventory.

Quantity(id).

Procure(id, n).

Ship(id, n).

Invoice()

}

// Set up some test data

type test struct {

id, qty int

}

// Nicely output if test fails/passes

var passFail = map[bool]string{false: "FAIL", true: "PASS"}

func main() {

// Test Cases

tests := []test{

{id: 10, qty: 101},

{id: 10, qty: 50},

{id: 20, qty: 50},

{id: 30, qty: 2},

{id: 30, qty: 1},

{id: 40, qty: 5},

}

expects := []inventory.OrderResult{inventory.Ordered, inventory.Fulfilled, inventory.Fulfilled, inventory.UnableToProcure, inventory.Fulfilled, inventory.UnableToProcure}

pass := true

for i, test := range tests {

result := Order(test.id, test.qty)

// None of our tests should ever result in RIGHT (there is no `error` thrown anywhere)

if result.Which() == either.RIGHT || result.Left() != expects[i] {

pass = false

}

fmt.Printf("[%s] ordering %d, qty: %d => %+v\n", passFail[result.Which() == either.RIGHT || expects[i] == result.Left()], test.id, test.qty, result.String())

}

if !pass {

fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "\nFAIL\n")

os.Exit(1)

}

fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "\nPASS\n")

os.Exit(0)

}When we go run main.go:

[PASS] ordering 10, qty: 101 => Ordered

[PASS] ordering 10, qty: 50 => Fulfilled

[PASS] ordering 20, qty: 50 => Fulfilled

[PASS] ordering 30, qty: 2 => Unable to procure

[PASS] ordering 30, qty: 1 => Fulfilled

[PASS] ordering 40, qty: 5 => Unable to procure

PASSWe get what we expected, everything under id:30 is procurable so we

get Ordered when not in stock, it's Fulfilled

when in stock, and Unable to procure when the item is not

in stock and we cannot order it.

All three branches of our business process tree are now handled and all three termination points within one call chain.

"Yea but hey! most of this business process can follow the

same pattern, what about something that doesn't?" There isn't much that

doesn't and in the case where you should follow very different logic

then you have the fallback to switch result.Which() and

follow the chains that way but this should be an exception if you're

thinking clearly.

That about does it for the business process as types. This shift in thinking is possible in most languages but it does require some forethought about the what the process is and what data is needed throughout the chain.