Why Visual and Speech Programming Aren't More Prevalent

// date: 2021-10-23

// filed: programming

// perma

Since the beginning of time when humans demanded computers make leisure more leisurely, they started trying different techniques to make visual programming become a thing. It's not prevalent and it likely won't be. My feeling is that speech programming likely has the same problems.

Information density is the biggest problem facing alternatives to typed or written languages. If you use the Lexical Density (LD) metrics for plain language writing versus speaking you find that most spoken language is about 40% efficient while written languages are closer to 60% 1. The method behind LD is that you remove filler words ("the", "an", etc) and analyze the text as a ratio of what's left to the total words. Up to the start of this sentence this article's LD is 55%. That means half of it is merely fluff for your reading pleasure.

Speech

Okay, a 20% deficit is what we're facing to bridge speech to text but

this doesn't quite paint the entire picture and ignores that it's a 33%

increase over its alternative. The language you need to tell a computer

what to do needs to change and the developer's language needs to

increase in precision as the problem becomes more complex. As a thought

experiment let's walk through how you'd tell a computer to implement

Levenshtein distance in plain English. The algorithm generates a number

representing how far apart two words are so let's compare

hello and world.

The algorithm in pseudo code:

func lev(a, b string) int {

if b.length == 0 { return a.length }

if a.length == 0 { return b.length }

if a[0] == b[0] {

return lev(a[1..], b[1..])

}

return 1 + min(lev(a[1..], b), lev(a, b[1..]), lev(a[1..], b[1..])

}If you were transcribing this to a computer it could look something like this:

00> Create function levenshtein with string arguments a and b with return type number.

01> In body levenshtein do the following.

02> If the length of b is zero then return the length of a.

03> If the length of a is zero then return the length of b.

04> If the first character of a equals the first character of b then return the result of function levenshtein using tail of a and tail of b.

05> return one plus the minimum of the following.

06> Function levenshtein using tail of a and all of b.

07> Function levenshtein using a and tail of b.

08> Function levenshtein with tail of a and tail of b.

09> End minimum.

10> End function.Take note of how poorly line six reads. If you were to say

tail of a and b then you could get either

a[1..], b[1..] or a[1..], b and both are

technically correct translations of English to beep boop.

This also demonstrates how how much expansion is required to go from text to speech. There's eight effective lines in the pseudo code and ten in the speech and the speech based example has much longer lines to describe what it wants.

Talking at the Computer

The density of the computer language is much higher than the spoken language's and once you're accustomed to reading and writing in this way it's really difficult to go back. There's a fella with a green tuxedo with yellow question marks asking you why would you ever choose to be so much less efficient? He's probably wearing white sneakers. If you did really want to make speech to program a thing then you'd have to go through the process of not only learning how to read and write in the computer's language but you'd have to become very proficient in it and many other pieces of computing like how would you deal with an Escanaban's accent?

If you back up and explore this topic further you can start looking

at math notation. It varies somewhat between areas of study but I don't

know of a single person who writes one plus one to mean

1+1. In English there is even the ligature of

et condensed to & to mean and

and that's saving us one key stroke for the writer by my reckoning and

two characters for the reader. Math notation takes a deep turn for most

people in the later years of high school and none are notated in plain

language. Why?

Math notation is very dense. It conveys complex information with a concision that spoken language cannot approach. Giving up this notation might only make it more friendly to newcomers but in order to get to a level where you could make this happen you have the same problem that computer languages have in trying to use speech. You have to become an expert in the notation you'd like to change and the systems surrounding it and by the time you do that you have to ask yourself if the loss of precision and concision is worth the effort and undertaking. Then you need to convince all the other nerds to also start using that notation and nerds care less about charisma than they do about being concise; we have other stuff to do, after all.

One math notation for the problem above (originally here):

lev(a,b): |a| if |b| = 0,

|b| if |a| = 0,

lev(tail(a), tail(b)) if a[0] = b[0],

1 + min( lev(tail(a), b), lev(a, tail(b)), lev(tail(a), tail(b)) )This ignores, of course, the expansion from math to code to language

of simple things like: a³ = a ** 3 = a cubed.

Come Again?

The final point here is that nearly all languages in the world, no matter how dense, approach about 39 bits per second2. The lower density languages like Japanese tend to speak faster resulting in a similar amount of information being conveyed by a denser language such as English.

Having a computer read back your code so you can interact with and gain context of what you might've been thinking a year ago seems more error-prone than just groking your code. Even humans interacting in real life tend to miscommunicate for a wide variety of reasons sometimes through neither person's fault. Even though we speak the same language we don't always do it similarly.

Visual Programming

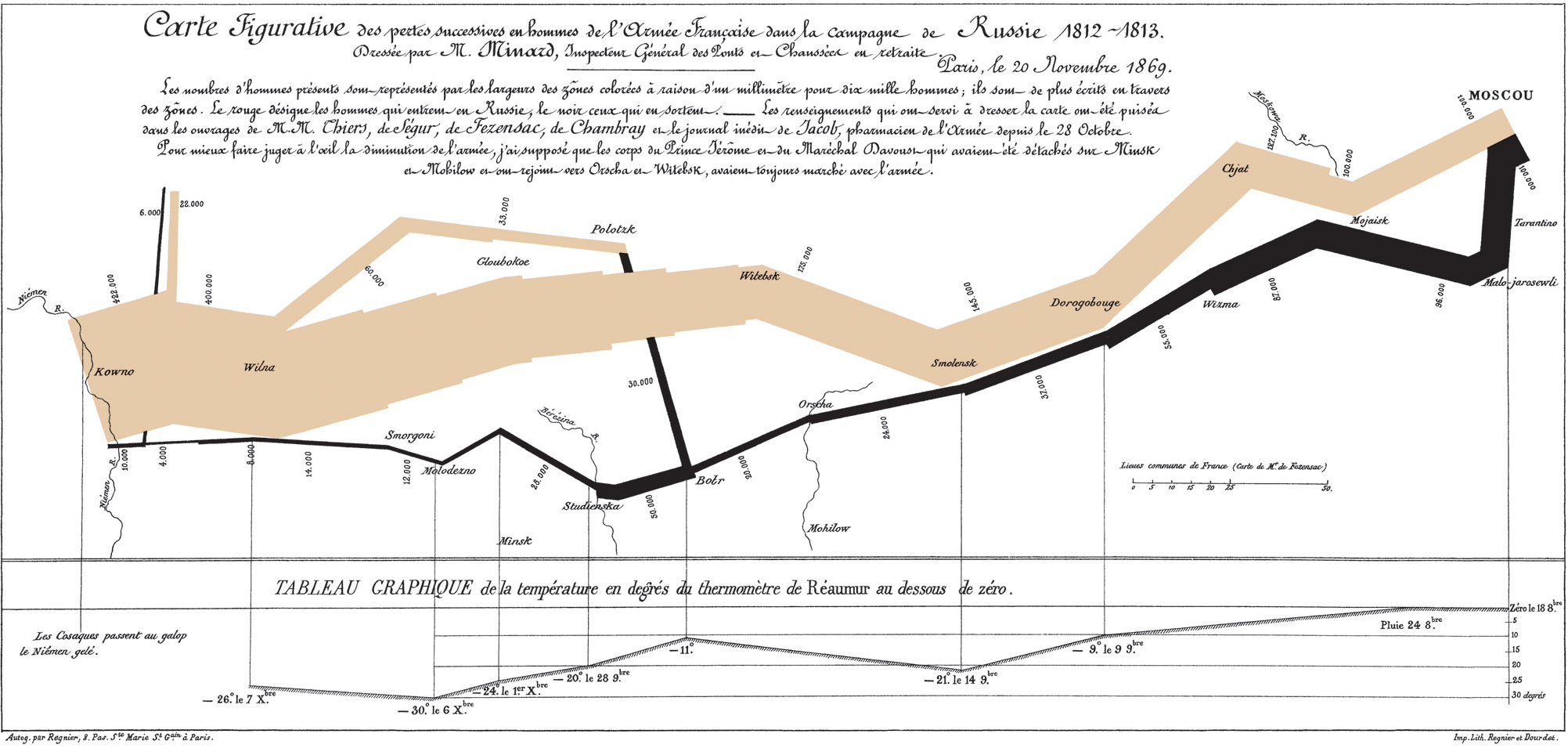

Visual programming becomes really strange when you consider that the things a computer is really good at. First, though, let's take a look at what a visual data representations look like. There are plenty to choose from so we'll look at someone who's top of class and also happens to have created the coolest chart in all history, Charles Minard.

A Chart

This chart is information dense and fairly concise. A great start. It beautifully shows the following data on Napoleon's army as they invaded and retreated from Russia:

- Troop strength

- Distance travelled

- Temperature

- The geolocation

- The Army's heading

- Location on <date>

So, we have an example of a complex system that is described [mostly]

visually. This is great, this is something we can start to work with and

it means that possibly someone will think the effort worth their time to

turn this type of programming into a reality. The very difficult part of

doing so is how do you represent an unknown on a chart? From the speech

example how do you describe an a visually? This is a

serious question and problem with charting and this is only included

here to show that it is possible to be concise in a picture.

The problem with converting these types of visualizations into robot language is that these charts and graphs display discrete data. They're not meant to display data that hasn't happened yet. Once the data are available then you don't have a problem of representing an unknown element visually and this is the rub, in order to code this way you'd need to know everything that could happen including their side effects.

Not realistic and absolutely unreal. Great, let's explore somethong more realistic.

GUI Based Programming

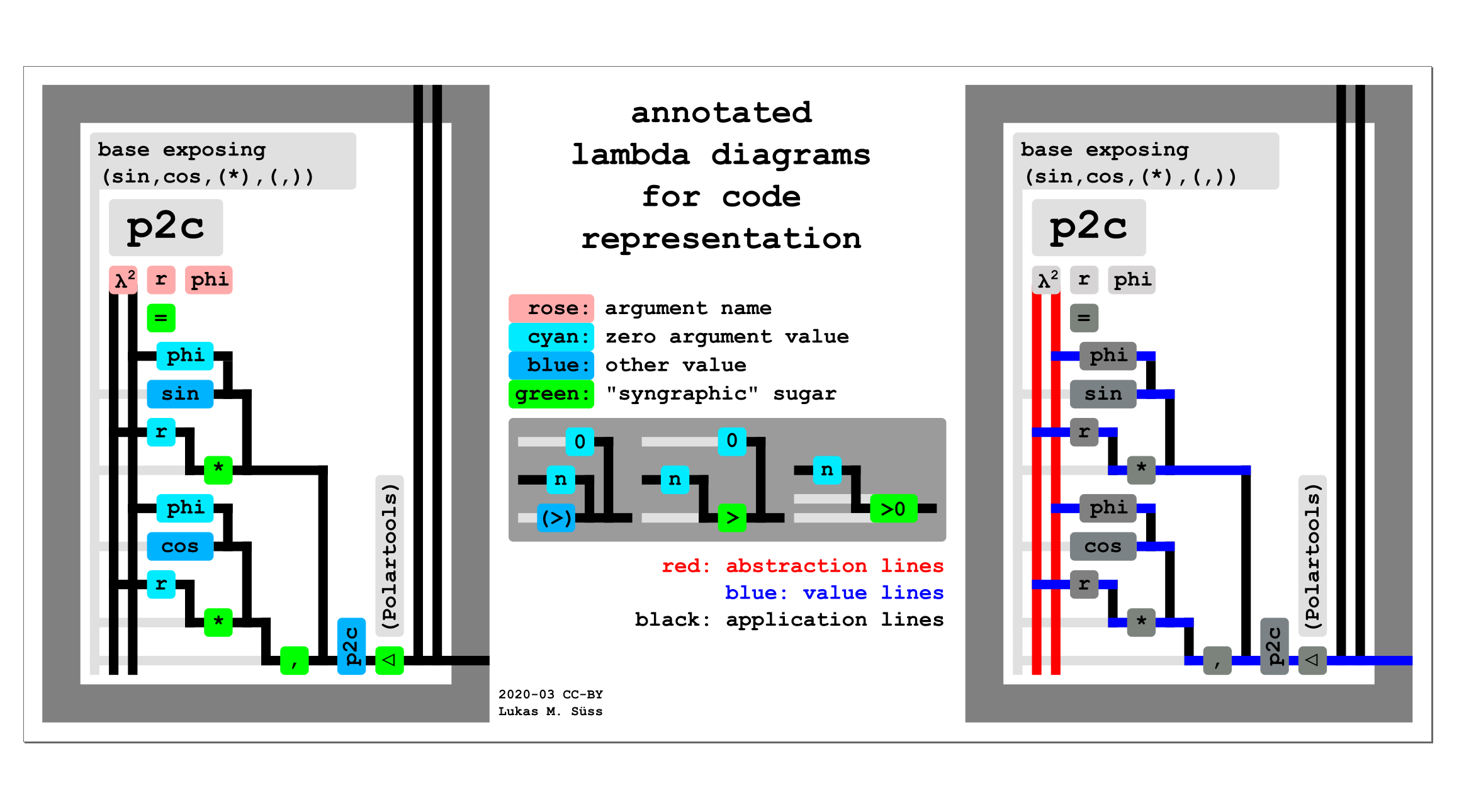

Let's explore some GUI based options, these are more widely available and don't require you to be Marcel Duchamp or subscribe to the church of Bauhaus. Here is one of the better illustrations floating around on the deep web today illustrating how to convert polar coordinates into Cartesian (grabbed from here).

Outstanding. This is a great illustration of what a computer language does when you tell it to do the conversion and looks a lot like an AST. Looks great albeit a little backwards from how one might think about it. Focusing on the left box, the input comes from the lower right and works its way to the upper left splitting x and y at the comma and doing the respective calculation and piping it back to, presumably, the caller.

Why is this not a thing? This visualization is great and I get it! A few reasons off the cuff, it's information poor. That visualization takes up half of a screen and the equivalent text is one line.

A more in depth analysis will take into account that as a programmer you must retain a large level of context in your mind. There is no shortcut to remembering the call stack and variable data that you're using to debug. If you're using breakpoints then that makes it easier but you still must remember a lot about data and state. Now, imagine you're debugging someone's work and the only information you have to go on is that the coordinates displayed to a user are wrong. You're now trying to grok an image (rather than written text) at every breakpoint and keep that state as you work your way through the malfunction.

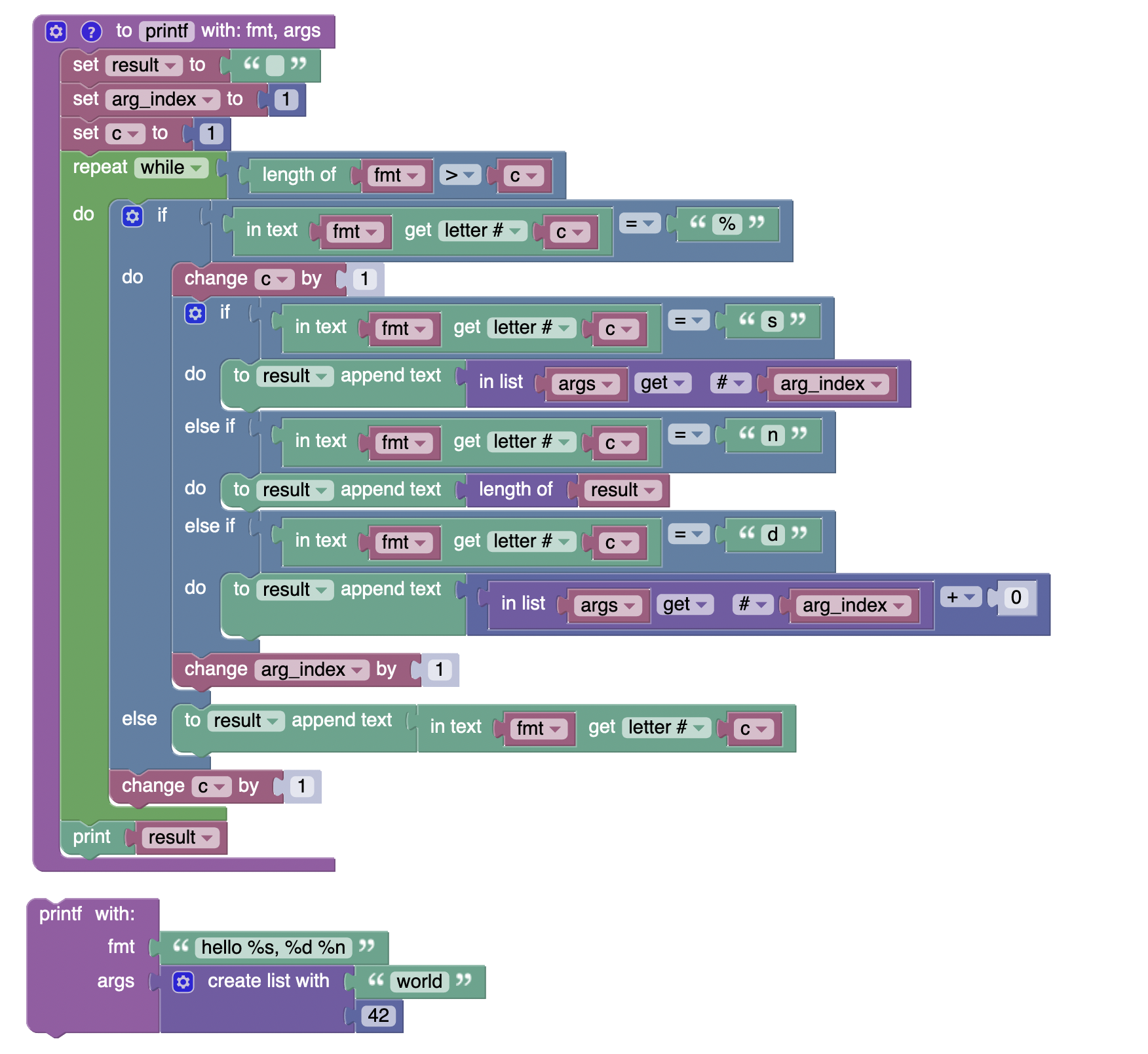

Let's dive into this hovel head first. How do you display a loop over

an unknown number of inputs? Most likely it looks like a feedback

circuit. How would you implement printf visually? This

turns into a spider web of filter statements as you check

variable types and locations with format breaks. Trying to visualize

this in a way that would work with any number of inputs and be something

you could look at became overwhelming visually. This problem is actually

difficult enough that a search for

"visual programming" printf turns up zilch.

Searching for a VPL to try and implement this function in also turned

up short. Blocky

fails to provide a way to call functions not defined in the program so

doing a variadic function became difficult when transpiled to javascript

as there was no way to call arguments. Here is a no frills

or error checking printf that can only handle

%s|d|n. Error checking was baked in and removed so that the

entirety of the function could be captured in one screen grab.

The novelty of clicking buttons to increment a counter by one quickly wore off and the resulting block looks like a color coded version of the text you'd end up writing anyway. At least in Forth the color isn't interfering with your ability to read.

Final Thoughts

Computers won't likely make the transition to speech based programming until spoken language becomes more dense and discrete. The idea of learning something so well as to speak its language fluently and then designing it to be less efficient seems absurd.

Similarly, visual programming has a similar problem where visualizing abstraction becomes tedious to write and read.

Perhaps in the next article we can explore running LD against programming languages and either support or pull the rug out from these ideas. Something like LD analysis for programming languages to support or pull the legs out from under this assertion.